By Charlie Botterell

I had always liked mental puzzles, and when I found out about the Kids Lit Quiz trivia competition in grade eight, it was as if my endless fountain of useless knowledge could be put to use. I was shocked by the fact that there were also other people in the world who were interested in the same things as me, and had an equal amount of trivial facts in their brains. It seemed like it had been made for me, and I was enthralled by the competitions and the buzzers, and I couldn’t wait to see what would come next.

Our trivia team had been preparing for this competition for months at that point, and I had been stressing about this competition for weeks. A month beforehand, our team had gone to provincials, and before that, regionals. We got past both by the skin of our teeth, with the gap between us and the team that didn’t make it being only one or two points. We knew we had to step up our game for the nationals, so we had been practicing nonstop after school every week doing the questions from previous year’s packs, and had been improving. After all of that, we felt prepared for the nationals.

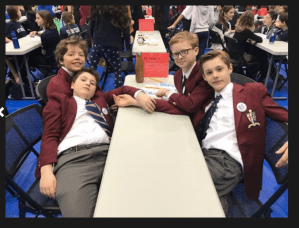

After school ended that day, our team took the subway to Sherbourne Station, and then walked over to the competition at Branksome Hall. Our team consisted of Ms. Kirkland (our coach), Jack Beatty, Jacob Lloyd, Oscar Tiplady, and me, a nervous grade eight student.

When we arrived, we saw the rest of the teams practicing, acting much more serious than us. When I looked at the quality and speed of their answers, they seemed like demigods to me, and we were just ants to crush on the way to internationals for them. The best team there was UTS (University of Toronto Schools), a team notorious for being incredibly good, even among such impressive competition.

We found a table to practice, put our backpacks down, and got to work practicing, in a last-ditch effort to prepare for our duel of wits to come. They brought in some pizzas, and we all dug in, being ravenous. After a while of eating and hanging out, we discovered that Oscar was nowhere to be seen. We waited and looked around for close to ten minutes, only to have him walk back in like he hadn’t been gone. Ms. Kirkland, who had been fretting over losing one of the students she’d brought, demanded to know where he had been. He informed us that he had simply been in the bathroom, and insisted that he let us know before he left, despite none of us remembering him saying anything. He sat down again and finished his pizza while we were all quietly laughing about a joke Jacob had made: the fictional game show “Where Is Oscar?”

An adult came into the room as we were all finishing up our food, and informed everybody that we were starting. All of the teams finished eating, and we all walked out in a double file towards the rooms where we were playing. It was a longer walk than I had thought it would be, with us walking up and down three or four flights of stairs, and even going outside to move into another part of the school. We sat down in the classroom with our opponents and, once again, Oscar had disappeared into the void. He walked in about a minute later, and we all quietly laughed again. He was shortly followed by the question reader for the game, and we shook hands and got to playing. It was a close game in the beginning, but we consistently pulled ahead throughout the later stages of the game. All the while we were joking among ourselves quietly about the obscurity of many of the questions, “Of course, what a logical answer!”, or by making a bad pun which I will spare you from reading now. By the end, we’d won, but not by a huge margin. We shook hands and congratulated each other on a game well played before leaving for our second game.

The other games passed in a blur, with us narrowly winning most of them. By the end of those matches, we had made it to the real competition. This was why everyone was there, and this match would be between the leading eight teams, deciding who would make it to internationals and who wouldn’t.

We went in about twenty minutes before the game, in front of the bleachers that I thought would remain empty, cynically thinking “who would want to watch a trivia competition?” We sat down around a table and an iPad, with seven other tables with iPads around the front for the other teams. The other teams sat down, and the iPads were turned on. They had a large red button, just begging to be pushed. Before anyone else could, Jacob pressed it and a loud “BEEEEEP!” rang out throughout the room. We were told about the conventions of how we should press the button, whether or not we could discuss answers with each other, and how the point system worked.

After the long and monotonous process of hearing all the rules, we waited and talked. I had been in competitions with one of the UTS members before, and I knew he was really good. We talked and joked among ourselves, with the occasional random button press breaking up the chatter. After a while, the lights went on. These were not the normal light bulbs seen in houses and schools, they were large, industrial, television lights, and I instantly felt hotter seeing them beating down on me. After waiting a while before the beginning of the game, I started to sweat, as I felt the oppressive heat of the lights bearing down on me, as if I was in an arid desert. Then, people started to come in, filing into the bleachers. I realized that my previous idea, a more cynical one, was wrong. The seats filled up to almost half, and a camera was set up, much to my surprise. As I was taking all of this in, I didn’t see my Dad come in and find a seat, but when I looked around I saw him sitting close to the back of the seats, near the top right from my point of view. Seeing him there made the stakes higher in my mind, and I remembered that this was the game I had been practicing for.

Then, we started getting ready for the game. We all understood that this was not the time for frivolous button pressing and joking around. The question reader came out and the atmosphere onstage immediately changed. This was what we had prepared and trained years for, and we weren’t about to mess it up. The camera started rolling and the game began.

The questions started, and I realized we were underprepared. The questions might as well have been in Serbian, for all it mattered to me. I didn’t know any of the extremely obscure questions, but I took solace in the fact that not many of the other teams were getting points, except for one. UTS was getting these questions right, and took a huge lead very early on. As the game went on we started to get more comfortable, and I started to contribute to our answers more. By the third quarter, UTS was in first, in second was another school whose name I have long forgotten, and in third, us. We were still worried about even being able to catch up to UTS, due to them having a lead of almost a thousand points. But, as the game went on, we were steadily gaining points. Meanwhile, UTS, as a result of getting a huge lead, became cocky, answering questions incorrectly, which cost them points. This was because when you answered a question right, you got three points, and when you got a question wrong, you lost two points. As we gained points and UTS lost points, they slowly dropped lower and lower on the scoreboard. As they started to notice this, their team became desperate, only worsening the problem. By the end of the game, we were in third, and UTS was in seventh out of eight. While this might not have been a huge win for us, I still saw it as an absolute win, and we were called up to get a pennant and some books in a large envelope to commemorate the occasion and our placing of third out of all of Canada.

Sadly, only the first place team went on to internationals, but this disappointment only lasted a few seconds, as I reminded myself that we still placed top three in Canada. However, I knew that this competition marked the end of an era for me, and I knew that because of my age, I couldn’t go to the Kids Lit Quiz again. Even despite that bittersweet ending, I was satisfied with how I did, and I continued to do trivia for years afterwards. I have always felt that trivia is more than just answering a bunch of dumb questions, and when I first did a major competition, I felt like I finally found something that I enjoyed, was good at, and had high stakes.